Grey-headed Flying-foxes roosting at Yarra Bend, Wurundjeri Country. Photo: Doug Gimesy

Victoria is home to the Grey-headed Flying-fox, one of the world’s largest flying mammals. Also known as fruit bats, flying-foxes forage on nectar and pollen from flowering trees, as well as fruit. Flying-foxes fly out to feed at night before returning at dawn to rest in large camps, often in our towns and cities.

Flying-foxes are travelling nomads. They can move vast distances across eastern Australia, depending on where their food is. Sometimes, big flowering events in native forests can draw in thousands of flying-foxes to feast on the blossom while it’s available.

Flying-foxes help to maintain healthy forests. As they feed at night, they pollinate flowers and disperse seeds of native trees.

Grey-headed Flying-foxes are a threatened species and important for our environment. But sometimes they can cause concern for some Victorians, particularly when they live or feed close to us.

Did you know?

Grey-headed Flying-foxes have excellent eyesight and a highly developed sense of smell, which they use to find food at night.

Victoria’s flying-fox map

Have you seen a flying-fox recently? You can add a sighting on the flying-fox map and help improve our understanding of flying-foxes across Victoria.

Victoria supports many flying-fox camps, also called colonies or roost sites. Camps can be used permanently, seasonally, or just sometimes. The number of flying-foxes in camps can change a lot, depending on the time of year and how much food is available around the camps. Find out more about flying-fox camps using the map below or at Victoria’s flying-fox camps.

To add a new flying-fox sighting, click on the flying-fox to the right of the Find Location bar, and then find and click the location on the map where you’ve seen a flying-fox.

To learn more about a flying-fox camp, click on the circles for location details and the latest monitoring estimates. More information on camps is available at Victoria’s flying-fox camps.

To find out about other flying-fox sightings, click on the flying-foxes to find details of when they were seen and what they were doing.

Explore the map in full screen mode

For an enhanced experience, view the flying-fox map in full screen mode. This version allows smoother zooming and panning, letting you easily navigate the map. View the full screen map.

If you need assistance using the flying-fox map, call our Customer Contact Centre on 136 186 or email wildlife@deeca.vic.gov.au to manually report flying-fox observations.

Interesting facts about flying-foxes

Flying-foxes are flying mammals from the Pteropididae (fruit bat) family. They have the largest body size of all bats.

Flying-foxes are flying mammals from the Pteropididae (fruit bat) family. They have the largest body size of all bats.

You may not notice them during the day, when they sleep wrapped up in their wings.

Flying-foxes have large eyes that are highly adapted for both day and night vision, and pointed ears, giving them their foxy appearance.

The most common flying-fox species in Victoria is the Grey-headed Flying-fox (Pteropus poliocephalus). Grey-headed Flying-foxes are the largest flying-foxes in Australia, and they can weigh up to 1.1 kg. In flight, their wings unfold into a wingspan up to one metre.

They have black wings and grey-black fur on their body, with an orange ruff around their neck and lighter grey fur on their heads.

Grey-headed Flying-foxes range across eastern Australia, from north Queensland along the east coast all the way through to south-east South Australia. In Victoria, Grey-headed Flying-foxes have been recorded across most regions, with fewer records in the northwest.

There are 3 other flying-fox (Pteropus) species on mainland Australia:

- Spectacled Flying-fox (Pteropus conspicillatus)

- Black Flying-fox (Pteropus alecto)

- Little Red Flying-fox (Pteropus scapulatus).

As the name suggests, the Little Red Flying-fox is the smallest flying-fox species, and sometimes visits flying-fox camps in Victoria, especially in northern Victoria. You can spot a Little Red Flying-fox by its smaller size and reddish-brown colour, including brown wings.

Little Red Flying-foxes like to hang out together in tight groups when roosting. They are even more nomadic than Grey-headed Flying-foxes, and occur across eastern, northern and Western Australia, venturing further inland in search of nectar-producing trees. Little Red Flying-foxes can gather in really large numbers, with some camps supporting more than one million animals when nectar is bountiful.

Photo credit: Grey-headed Flying-fox stretching its wings on Gunaikurnai Country. Photo: Andrew Geschke.

Grey-headed Flying-foxes feed at night on flowers (pollen and nectar) and fruit from a more than 100 species of native trees, as well as introduced species.

Eucalypt blossoms are their favourite, but they’ll also feed from paperbarks, grevilleas, banksias and other plant species. Flying-foxes use their long tongues to extract the nectar and pollen.

While flying-foxes can fly up to 100 km away from their camp at night to find food, most prefer to feed closer to home, within about 20 km.

You might see Grey-headed Flying-foxes in your garden at night, as they’re fond of native and introduced fruits such as figs and lilly pilly. Flying-foxes chew up fruit to get the juice, before spitting out the remaining pulp. Sometimes they’ll also eat leaves.

Grey-headed Flying-fox feeding on eucalypt blossom, Bunurong Country. Photo: Doug Gimesy.

Foods for flying-foxes are usually only available for a short time, while each tree species is flowering or fruiting. Flying-foxes are very mobile, which helps them find these rare resources across really big areas.

Researchers have found that Grey-headed Flying-foxes will fly on average about 1,500 km a year between camps. Some individuals travel much further!

The animation below shows the incredible nomadic movements of three GPS-tracked Grey-headed Flying-foxes across six months in 2023, as they travel from New South Wales into Victoria before visiting flying-fox camps across the state.

Tracking the flight path of three GPS-tracked Grey-headed Flying-foxes, showing nomadic movements in Victoria in 2023. Animation: animalecologylab.org, unpublished data.

Flying-foxes are busy looking after our native forests. While they’re out foraging at night, they spread pollen over long distances while feeding on blossom. This helps to pollinate native trees and improve their genetic health.

Flying-foxes can also disperse seeds across the landscape, boosting forest regeneration. By supporting forest health, flying-foxes help provide habitat for other plants and animals.

Grey-headed Flying-fox carrying a pup, Bunurong Country. Photo: Doug Gimesy.

Grey-headed Flying-foxes are social animals with some fascinating behaviours.

If you’ve passed a Grey-headed Flying-fox camp, you would notice that they’re very vocal animals. They use sounds to communicate with each other and many different unique calls have been identified. Calls have different meanings associated with behaviours such as mating, finding young in the camp and territorial disputes.

Australian flying-foxes are most active at night. They spend the day sleeping, interacting and resting. But towards dusk each evening, their camps come alive, as adults and adolescents get ready to fly out for a night of feeding. They spend the night hours foraging across the landscape. Just before dawn they return to roost, at the camp they stayed at the day before, or at a different site.

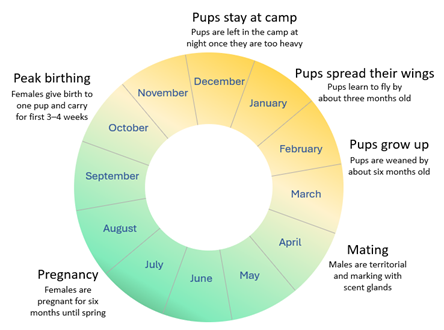

Autumn is mating season for Grey-headed Flying-foxes, with males becoming especially rowdy and territorial to attract mates. They scent-mark their territories using special glands on their shoulders. Flying-foxes usually conceive in March and April, and females give birth to a single pup 6 months later in spring.

For the first month or so, the mother will nurse and carry her pup while she’s out foraging, until it becomes too heavy to carry. Pups are then left in the camp at night while the mothers fly out to feed. When the mothers return, they can find their young by their call and smell. After about 3 months, the pups can start to fly by themselves and venture out at night to look for food. They are weaned and become independent by about 6 months.

Life cycle of Grey-headed Flying-foxes

The Grey-headed Flying-fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) is listed as vulnerable both in Victoria under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (FFG Act), nationally under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) and internationally under the IUCN Red List.

Flying-foxes usually rely on unpredictable food sources spread over an extensive area. The primary threat to Grey-headed Flying-foxes is destruction of their habitat, particularly foraging habitat. Flying-foxes are especially vulnerable to loss of trees that flower in winter and spring. Food shortages at this time can affect the ability of female flying-foxes to successfully raise pups.

Flying-foxes are also impacted by extreme heat, entanglement in fruit netting and barbed wire, and electrocution on powerlines. Climate change is likely to exacerbate threats such as extreme heat, habitat loss and food shortages, leading to increased mortality and reduced reproductive success.

To find out more about flying-foxes and extreme heat and DEECA’s approach to responding to heat stress events, visit extreme heat events and wildlife.

For more information on threats, see the National Recovery Plan for the Grey-headed Flying-fox or the IUCN Red List.

Grey-headed Flying-fox dipping its belly in water, Bunurong Country. Photo: Doug Gimesy.

Help for injured wildlife tool

Do you need to find help for injured native wildlife in Victoria?

Our wildlife tool will help you locate and contact the closest relevant wildlife carers and rescue and rehabilitation organisations to help the injured animal.

Page last updated: 07/04/25